“So I’m now going to blog about @peterjukes & his family,” wrote Dennis Rice…

TabloidTroll wrote: “If @PeterJukes writes any shit on me in his book the gloves will really come off. Newsnight ex wife, business failures.” The fact the mother of my two children had been made a target was pretty disturbing.

UPDATE (January 2015): Peter Jukes’ book was originally published as a PDF in August 2014; it was subsequently revised and expanded for the print edition, which appeared in September. This blog entry has been updated to include extra material contained in the revised version, and to provide details of Rice’s complaint to IPSO.

***

Sections

Introduction

Dennis Rice as hacking victim

Dennis Rice turns on Peter Jukes

Peter Jukes “investigated”

Appendix 1: The anonymous texts

Appendix 2: Press Gazette and IPSO

Appendix 3: Is Rice TabloidTroll?

Appendix 4: Rice calls in the Police

Introduction

Peter Jukes’ book Beyond Contempt: The Inside Story of the Phone Hacking Trial includes several passages about an attempt to intimidate him from writing freely by threatening to intrude on his personal family and financial circumstances. The threats were made by Dennis Rice on Twitter, both under his his own name as @dennisricemedia and as the sockpuppet @tabloidtroll.

This was of some interest to me as I was also targeted by Rice in 2013, after agreeing publicly with overwhelming evidence that Rice was running the @tabloidtroll Twitter account: he published a grotesquely unpleasant “attack blog” which included lies and distortions not just about me but also about members of my family. It even included a fabricated screenshot that purported to show that I use a dating site (I don’t, and never have). Full details here.

Why this is important

Dennis Rice is not just a “basement troll” – his journalistic career includes stints as Chief Reporter at the Daily Express and Investigations Editor at the Mail on Sunday. As “Tabloid Troll”, he also enjoyed the support and collusion of Neil Wallis, the former Deputy Editor of the News of the World. Rice’s bullying and reckless dishonesty therefore have significant repercussions at a time when the morality and integrity of tabloid journalism in the UK are under close scrutiny.

Dennis Rice as hacking victim

Rice is in an unusual position: he was formerly investigations editor of the Mail on Sunday, but he was also himself a victim of phone-hacking by rivals at the News of the World who were looking to steal a scoop about the then-Deputy Prime Minister, John Prescott. Details appeared in a recent article by Roy Greenslade:

The [Mail on Sunday’s] managing editor, John Wellington, spoke to Rice and [Laura] Collins in October 2006 – two months after [Clive] Goodman and [Glenn] Mulcaire were arrested – about the police having informed him that their mobile phones had been hacked between April and July 2006.

…Rice recalls that he was first called by the police, who told him he had been hacked 80 times, before he discussed it with Wellington. He later discovered that his office computer had also been hacked…

But the four were not required to be prosecution witnesses against Mulcaire. Wellington, who remained unaware of the computer hacking, said the police approached the paper so that its staff could change their mobile pin numbers.

Greenslade doesn’t delve into why Wellington “remained unaware of the computer hacking”.

However, and strangely, Rice has published a Storify piece that heavily implies that the contact with police came later. Specifically, he says that he had received correspondence from Hacked Off, which lobbies for press regulation, inviting him to attend a seminar on “our perspectives on how the Leveson Inquiry is going”. This arrived next to “an email about my tickets for London 2012”. He continues:

Two months earlier I had been called into New Scotland Yard and played a series of recordings which had been seized from the home of Glen Mulcaire.

They were messages left on my phone from friends, family, and work colleagues. In prosecution terms they were dynamite – pure indisputable proof of phone hacking.

The date implied here for his contact with police is April 2012. Perhaps this means that although Rice was told about his phone being hacked in 2006, the recordings did not come to light until 6 years later, although it’s odd he makes no reference to 2006 in his post. Further:

I remember being advised via a very capable lawyer that the best way to get out of this hole was to launch a civil claim, as police would not want the court to hear their witness had received a settlement from News International.

But Rice’s civil claim was lodged in 2011 and settled in February 2012; for some reason, he’s a year out.

Rice retained the services of the lawyer Mark Lewis, and he and his family members received confidential civil settlements. Lewis is well-known as the lawyer for the Dowler family, and he has achieved a high profile as a campaigning activist on the subject of phone-hacking by journalists. He has advised Hacked Off, and he was himself the target of an attempted smear by the News of the World. Lewis has described Rice as “a really great bloke. Old fashioned journalist. I know him well”, and, frustratingly, he appears to have accepted uncritically Rice’s counter-narrative that Tim was harassing him, rather than the other way around.

However, Rice is bitterly opposed to Hacked Off, and he refers to his own status as a hacking victim as evidence that some hacking victims do not want to see the scandal lead to press regulation.

Dennis Rice turns on Peter Jukes

Rice, it should be remembered, maintains that he is not TabloidTroll – he has even written to Google, declaring “under penalty of perjury” that ” I am not responsible for this anonymous account (tabloidtroll)”. Peter’s book does not make any statement that contradicts this, although his narrative leaves us to draw our own conclusions.

For a long time, Rice as TabloidTroll enjoyed bantering with Peter, but things turned nasty after Peter drew a distinction between being hacked and finding your private life in a newspaper, and being hacked for purposes of industrial espionage. Of course it’s a horrible violation to be phone-hacked, even if private messages do not find their way into the public domain, but Rice’s reaction verged on hysteria. Peter writes:

Rice took exception to this and told me that his family had been targeted. I replied I was very sorry to hear that and updated my blog. This failed to placate Rice, who accused me of “stalking” him on Linked In (he’d come up in a search I’d done when writing up his timeline from the trial). He added that he was a potential witness, and I was “harassing” him so he was thinking of reporting me to the Attorney General…

Rice… somehow read my blog as demeaning journalists as second-class citizens. “It’s now 24 hrs since I showed @peterjukes that his smear blog about my family was factually incorrect,” he tweeted, “yet he still refuses to alter it. So I’m now going to blog about @peterjukes & his family.” There were some mutterings about me being too afraid to meet him face to face.

I was more concerned about.the tone of his subsequent comments. “His blatant refusal to remove these falsehoods invites me to look as an investigative journalist what else is going on here,” Rice tweeted about my “malicious” “smear blog,” saying I was “wetting your pants when a real journalist turns his gaze on you. I’m coming.” I was not sure what Rice meant when he said he was “coming,” though I knew he had taunted someone else on Twitter after doing financial checks at Companies House. Through the months ahead I anxiously anticipated some kind of blog about my financial background or my family. Rice locked down his feed again.

Another account, TabloidTroll (which Rice vigorously insists he has nothing to do with) mentioned me regularly, my crowd-funding, and even suggested I should give some of the proceeds to my ex-wife.

This is a pattern with Rice; creepy messages of a goading and self-evidently harassing nature, which attempt to justify personal intrusion by projecting his own malice onto his target. Peter hadn’t written anything about Rice’s family other than to acknowledge they’d been hacked; there was absolutely nothing that could reasonably provoke “a taste of his own medicine” threat. Rice’s outrage was either hysterical or affected.

Peter Jukes “investigated”

Later in the book, Peter explains what happened as publication approached:

Now there was no danger of contempt, I tweeted out that this book would contain some of the background stories about pressure during the trial.

Soon, TabloidTroll was back on Twitter, writing: “If @PeterJukes writes any shit on me in his book the gloves will really come off. Newsnight ex wife, business failures.” The fact the mother of my two children had been made a target was pretty disturbing. As for “business failures,” I crowd-funded my tweets because my earnings from freelance journalism were insupportably low (though I love the job.)

A week or so later I received some anonymous texts mentioning vague legal threats and hoping I would “enjoy the weekend.” Some other Twitter accounts (which I didn’t see at the time) also wished me well for the weekend, and suggested some kind of “Daily Mail Tuesday.”

I recall seeing the Tweets at the time; one, which was quickly deleted, was from an obscure account controlled by a man who I know had helped Rice write the unpleasant blog about my mother; another one was an anonymous and abusive troll account that also carried goading comments about Tim and his partner. The account used the photo of a plus-size woman who had nothing to do with any of this; when her friend asked the author to remove the photo, he responded by saying that the woman should apologise for being ugly. The account was then deleted, although a copy has been saved.

As predicted by the Tweets, Peter was then approached by a journalist with the Daily Mail named Richard Marsden, who told him “he’d been handed an anonymised email with personal financial details and a separate piece of paper with my email address and mobile phone number”.

The allegation was that Peter had lied about needing funding for a mortgage repayment, when in fact he supposedly had no mortgage; the same details were also passed to @MediaGuido, a Twitter stream and website associated with Paul Staines’ Guido Fawkes’ Blog. @MediaGuido fired a couple of inquisitorial Tweets in Peter’s direction (here and here). Peter continues:

I explained to [Marsden] calmly that there was no mortgage on my property because I had sold it two weeks previously. I could easily prove I had quite a sizeable mortgage until then… It was an embarrassing mistake for them: it was a false, non-story. Soon afterwards Tabloid Troll closed down and deleted his account.

In September, @MediaGuido conceded to Peter – with poor grace – that:

It was a dud tip resulting in no story except you claiming victimhood. We followed it up and it led nowhere.

@MediaGuido then added to me:

We know who gave us tip and we now know they made a mistake.

Peter doesn’t claim that the attempted “exposure” was down to Rice; again, readers must draw their own conclusion. Rice also had other possible motives for closing the account: a number of TabloidTroll Tweets easily showed that Rice was the account holder, and I was starting to involve the authorities over his threats to visit my mother. TabloidTroll’s own story was that he was going offline to write a book, although of course that would not necessitate deleting the account.

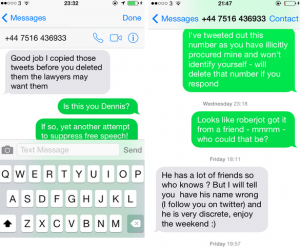

Appendix 1: The anonymous texts

The anonymous texts remain a mystery – as can be seen above, the author falsely accuses Peter of having deleted material. On Twitter, Peter wondered how the sender had acquired his mobile number, and suggested that a breach of the Data Protection Act may have occurred. This prompted an interjection from a man named Andrew Roberjot (@frankiescar), who said: “I just asked a friend of mine who knows you for your mobile number, they gave it to me, How is that illegal?”

Peter then noted that his mobile number was known to Neil Wallis, the former deputy editor of the News of the World, and that Wallis had just recently before described Roberjot as his “drinking buddy”. Peter then confirmed that Wallis had his mobile number; this in turn prompted Wallis to accuse Peter of making “ludicrous allegations”. Roberjot then explained he had received the number from someone else, that he had just made the comment “to prove a point”, and that he hadn’t passed the number on to anyone else. The result of all this back-and-forth, which had been triggered by Roberjot’s initial comment, was that the question of who had actually sent Peter the crank texts was hopelessly beclouded. Perhaps that was the point.

Appendix 2: Press Gazette and IPSO

In August, Press Gazette published an article by Peter, headlined “How Peter Jukes invented a new way of funding court reporting and found himself investigated by the press”. It included details of the threat emanating from the TabloidTroll account to write about “Newsnight ex wife, business failures”, and the subsequent anonymous texts and botched mortgage smear.

The original version also referenced the threat which Dennis Rice made under his own name to write about Peter’s family, but this section of the article was removed after Rice made a complaint. This is because Peter’s text gave the impression that both Tweets had appeared around the same time in June, when Rice’s @dennisricemedia Tweet had actually been in January.

The error had slipped in because Rice’s January Tweet had become the focus of renewed interest in June, when he made his very similar comment as TabloidTroll. Evan Harris RTed both at this time, in order to show their obvious common authorship:

The mask slips RT @tabloidtroll If @PeterJukes writes any shit on me in his book the gloves will really come off. ex wife, business failures

— Dr Evan Harris (@DrEvanHarris) June 29, 2014

(Same) mask slips RT @dennisricemedia So I’m now going to blog about @peterjukes & his family, so he can enjoy a taste of his own medicine.

— Dr Evan Harris (@DrEvanHarris) June 29, 2014

That was on 29 June; Rice protected his @dennisricemedia account the next day, making it impossible for non-followers to verify the quote. Rice did later make his account unprotected again for part of July, but he reverted back to private a couple of days before the mortgage smear was deployed. This meant that when Peter subsequently gathered evidence of Rice’s hostility, the June RT of the January tweet resulted an error in chronology. But Rice was using a sockpuppet to make exactly the same threat in June.

Rice has since deleted the January Tweet, and he’s now threatening legal action against Peter if he republishes @dennisricemedia tweets.

Press Gazette also issued a correction, which includes the following:

…It quoted a Tweet from Rice to Jukes which read: “So I am now going to write a blog about @peterjukes and his family – so he can enjoy a taste of his own medicine.” The extract mistakenly gave the impression that this message was sent in June 2014, around the time of a dispute over the reporting of the cost of the hacking trial.

In fact Rice posted the Tweet in January. He said it was in response to a tweet from the author which read: “You were hacked over a story about someone else’s private life Dennis. Yours was never outed.”

…Press Gazette has removed the reference to Dennis Rice from the article and would like to apologise to him for the mistake, and for not offering him right of reply in advance of publishing the extract.

Predictably, this was not enough to satisfy Rice, who went on to make a complaint to IPSO, the new press regulator. IPSO published its judgement in January 2015:

11. The journalist said that the complainant’s Twitter account had been “protected” at the time the article was written. The source of his information was therefore a retweet by another individual.

12. On balance, the Committee concluded that in these circumstances additional steps should have been taken to ensure the accuracy of the claim for the following reasons. First, the journalist was relying on second-hand information from a highly flexible medium in which misunderstandings can occur. Second, the tweet – and in particular, the timing of the tweet – was presented in a context that suggested the complainant was threatening to write about the journalist’s family as a response to the disclosures about his funding, when in fact the tweet had been written before that information had entered the public domain.

13. While the journalist said he believed that the retweet was contemporaneous – as was likely to be the case, given the nature of the medium – in these circumstances, the complainant should have been contacted to check the claims, or other steps should have been taken to verify the nature and timing of the tweet. Indeed, the website acknowledged that it should have provided him with the opportunity to comment on the claim before publication. The failure to do so breached Clause 1 (i). This aspect of the complaint was upheld.

However (emphasis added):

21. The Committee considered both the nature of the breach of Clause 1 of the Code and the resulting inaccuracy. While it had concluded, on balance, that the complainant should have been contacted to check the claims, or that other steps should have been taken to verify the nature and timing of the tweet, the Committee did not consider this to be an egregious failure. The breach of Clause 1 (i) was not so serious as to warrant a requirement that the website publish a critical adjudication. Nonetheless, it was not in dispute that the result had been a significant inaccuracy with the potential to affect the complainant’s reputation. The appropriate remedial action was the publication of a correction.

Rice’s complaint also contained other elements, all of which were rejected. IPSO found that the correction had been made promptly, and it ruled that Rice had no grounds to complain that he had not been given right of reply, because he had not asked for it. Rice further made a typically hysterical and ludicrous accusation that the article had violated his privacy. IPSO gave that short shrift:

The information contained in the article related only to the complainant’s comments on a matter which could not be considered to be private. Their publication did not constitute an intrusion into the complainant’s private life, and as such, no justification was required under the terms of Clause 3.

Rice also wanted the entire article removed, which shows that Rice’s motive for making the complaint was not to protect his own reputation, but to damage Peter’s.

As expected, Rice and Media Guido have sought to build a scandal around the IPSO finding, even though it adds nothing of substance that was not in the original Press Gazette correction in August. And also as expected, their new outpourings contain exaggerations and falsehoods: in a snarky blog entry, Media Guido states that “Press Gazette has now apologised for publishing the Jukes extract”, when in fact the site has merely restated its original correction, while Rice is spreading the false claim that Press Gazette has “pulled” the article, when in fact it is still on-line and can be seen here.

Of course errors must be acknowledged and fixed, and, where appropriate, apologies given; but this is a desperate attempt to milk a minor mistake. It remains the case that Rice, under his own name, threatened to go after Peter’s family, not for any legitimate public interest reason, but to pursue private revenge; and IPSO of course paid no attention to the fact that Rice was saying almost exactly the same things in June as @tabloidtroll as he was in January as @dennisricemedia.

Appendix 3: Is Rice TabloidTroll?

Rice has always maintained that he was not TabloidTroll, and he has made complaints to Google telling them to remove links to sites where the evidence is published. Rice says that “two police forces” have confirmed that he was not running the account; also, Roberjot also claims to have met TabloidTroll, and to be able to confirm that he’s not Dennis Rice.

However, this is not sustainable.

1. Rice apparently complained to Thames Valley Police about being named as TabloidTroll; that hardly amounts to a police force “confirming” he was not running the account, and it seems likely that his (unsubstantiated) complaint was based on privacy rather than inaccuracy.

2. A complaint about Rice’s threats as TabloidTroll made to Surrey Police foundered after a @tabloidtroll Tweet appeared at a time when Rice had an alibi. But that could easily be arranged by a friend or by automatic scheduling.

3. Roberjot has also said that a photo of Rice posted by Press Gazette to Flickr some time ago (unrelated to Peter’s story and recently removed after it came to wider attention) is actually a photo of someone else. But I know for a fact that the photo indeed is of the correct person.

4. Evidence supporting common authorship includes an IP correspondence between an email sent by Rice and a visit to a website made when TabloidTroll clicked on a link, and an academic linguistic analysis by Dr Nicci MacLeod from the Centre for Forensic Linguistics.

Further, during 2014 Rice made two phone calls to my mother, despite being told not to repeat his first approach. In the second call, he told her sharply that I’d “better be” at her home on a certain day, then hung up; TabloidTroll then announced his attention to come to her address. This gave me no choice other than to involve police, who warned him off, and I have a copy of an email in which the officer involved states that Rice has “taken his ‘tabloidtroll’ account off line” (this was was from a subject-access request; Rice’s name is blanked out, but it’s obviously him).

There are also other lines of evidence, which I will not go into here.

Appendix 4: Rice calls in the police

The original version of this post appeared in August 2014. Several weeks later, Rice went to police in High Wycombe to complain that my writings about him amounted to harassment. As a result of this, I was issued with a Police Information Notice, warning me that if I mentioned Rice’s name again I would be investigated for harassment.

The PIN specifically states that “the police are not commenting on the truth of this allegation”, but Rice inevitably could not resist publicising its existence as evidence of criminality. I therefore put the record straight, which then meant I had to attend an “voluntary” interview at High Wycombe under threat of arrest (also as expected, an anonymous troll account on Twitter that sends abuse in my direction started making comments about High Wycombe).

I was interviewed by a PC, and her sergeant decided shortly afterwards that there would be no further action. My lawyer at the interview (a specialist from Bindmans) advised me that the PIN amounted to censorship and that any arrest would have been a wrongful arrest. I am currently in the process of pursuing a formal complaint against Thames Valley Police, and hope to write more about this soon.

Fuller details here:

Filed under: Uncategorized | 3 Comments »