The recent ITV documentary Rachel Nickell: The Untold Story (for KEO Films, written and presented by Fiona Bruce ) is a good opportunity for renewed critical focus on the practice of criminal profiling and its influence on police investigations.

Nickell’s murder in 1992 – in broad daylight on Wimbledon Common, in front of her young son – prompted the Metropolitan Police to seek advice from a profiler named Paul Britton. Britton had previously worked with police on a series of unsolved rapes along southeast London’s Green Chain Walk, and a year after becoming involved with the Nickell case he advised on the profile of the unknown killer of a single mother named Samantha Bisset and her four-year-old daughter Jazmine, again in the same part of the city.

We now know that the perpetrator in all three cases was a man named Robert Napper. However, as Fiona Bruce explains in the documentary, Britton “created three different criminal profiles” before Napper was identified – an unanswerable indictment of the methods used.

Notoriously, Britton’s involvement in the Nickell case was significant in convincing the police that the killer was Colin Stagg, a man living nearby who had no forensic link to the crime scene. Stagg was in prison on remand when the Bisset killings occurred, but this did not shake the confidence of the Nickell detectives, even though police dealing with the Bisset case had consulted them and the similarities between the two incidents were obvious even from media reports. This latter point is discussed in the documentary by Bill Clegg QC, who was working on Stagg’s defence:

I remember reading the papers in chambers, and within two or three hours I came out of the room and said to my clerk, “I reckon that’s the man that killed Rachel Nickell”. It seemed to me to be perfectly obvious. Statistically, it’s extremely rare for a mother to be murdered in the presence of a young child.

Detective Mike Banks, who led the Bisset investigation, gave Bruce this assessment of Britton’s contribution:

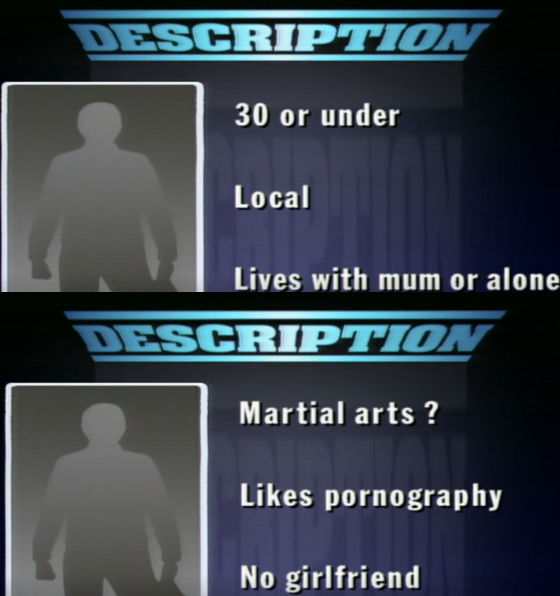

It wasn’t my request, I was told to get him in… Very nice chap. But I think one of my youngest DCs gave exactly the same outline of who he thought would be responsible as what Paul Britton came up with.

Footage from Crimewatch shows Britton suggesting the “possibility” that the Bisset killer might be wanting to call into the programme to talk to him.

Bruce also spoke with Professor David Canter on the limitations of criminal profiling; according to Canter:

People think that it’s some clever, insightful individual that really owes more to Sherlock Holmes actually than to scientific psychology. For a start, to actually say you can indicate something about a person from the brief details you got at a crime scene is really speculative… We can’t know what people are feeling and thinking, particularly criminals, who often don’t even know themselves exactly what’s going through their minds at the time.

Canter is the founder of the International Research Centre of Investigative Psychology at the University of Huddersfield, and the author of Investigative Psychology: Offender Profiling and the Analysis of Criminal Action; his centre “compiled a report on the eyewitness testimony that was crucial in convicting Al Megrahi as the Lockerbie Bomber”.

Bruce’s decision to use Canter as Britton’s peer critic sidestepped a broader debate about whether criminal profiling is of any value whatsoever. The work of Professor Craig Jackson of Birmingham City University is significant here, and his criticisms brought him some media attention in 2010:

…according to a team of psychologists at Birmingham City University, the practice of offender profiling is deeply unscientific and risks bringing the field into disrepute.

In many cases, offender profiles are so vague as to be meaningless, according to psychologist Craig Jackson. At best, they have little impact on murder investigations; at worst they risk misleading investigators and waste police time, he said.

The journalist Nick Cohen summed it up nicely in 2008, when it was at last confirmed that Napper had killed Nickell:

Britton would never have impressed detectives if he had said that Stagg was a bit of a weirdo. When he dressed up that same thought in psychological language and talked of “deviant interests” and “sexual dysfunctions”, he sounded fatally convincing.

…Genetic fingerprinting catches the guilty and frees the innocent. Psychological profiling traps the innocent and sends the guilty out to kill again.

Cohen had previously written about Britton in 2000, noting his media profile:

His case shows that once your name is in the newspaper contacts files and BBC libraries as the authoritative expert without compare you can elbow out competitors and ensure your fame stretches to the crack of doom. Whenever there is an unsolved crime to discuss or an opinion is needed on the effects of Hollywood violence on the young, Britton is called for his view by everyone from the Sunday Times to the Today programme.

It should be remembered that profiling is used not only to identify suspects, but as expert evidence in trials. The most famous example how this can contribute to a miscarriage of justice is the case of Randall Adams, as discussed in Errol Morris’s celebrated 1988 documentary The Thin Blue Line. Adams – an innocent man accused of fatally shooting a police officer – was diagnosed as a dangerous killer by Jim Grigson, a forensic psychiatrist nicknamed “Dr Death” for his testimony in capital cases in Texas. Grigson’s pseudo-assessment of Adams was based at least in part in how Adams answered questions about the meanings of various proverbs.

Excurcus

Britton’s profiling skills is just one strand in the ITV documentary, which also discusses in some detail the police’s ludicrous “honeytrap” plot to get Stagg to confess. The programme says that the officer chosen for the task was “guided” by Britton; the judge at Stagg’s trial, Mr Justice Ognall, described Britton as the “puppet master”, although it seems to me that the police must take most of the responsibility for the fiasco.

Famously, the “honeytrap” (which never elicited a confession anyway) led the judge to declare a mistrial, which meant that Stagg was acquitted – but not exonerated. Police continued to maintain that Stagg was guilty, and he and the judge were subsequently subjected to tabloid monsterings. Some of this is mentioned in the documentary, but not the most egregious example, in which the Sun juxtaposed Stagg’s face with the headline “No Girl is Safe”. Such reporting can be seen as a precursor for the media vilification of Christopher Jefferies more than 15 years later.

Bruce’s view, based on her memories of reporting on the Nickell case at the time, is that police had taken the Nickell killing personality, and she “felt as if they’d all slightly fallen in love with her”. As such, they “lost objectivity”.

Footnote

(1) Britton was cleared of misconduct by the British Psychological Society in 2002, on the grounds that he could not get a fair hearing. He also maintains that he advised police to broaden the Nickell investigation, and that he referred back to the Green Chain rapes. However, according to the Telegraph:

His account contradicts a book he wrote 10 years ago, The Jigsaw Man, in which he said there was no link between Miss Nickell’s murder and Green Chain Walk attacks, but he now insists he was guided away from his original views at the insistence of senior detectives.

Filed under: Uncategorized | 1 Comment »