From the website of the Church of England, and widely reported:

An Abuse of Faith, the independent report by Dame Moira Gibb into the Church’s handling of the Bishop Peter Ball case, has been published today. Peter Ball was convicted in 2015 of misconduct in public office and indecent assaults against teenagers and young men. The report was commissioned by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, following the conviction.

In her foreword Dame Moira states:

“This report considers the serious sexual wrongdoing of Peter Ball, a bishop of the Church of England who abused many boys and men over a period of twenty years or more. That is shocking in itself but is compounded by the failure of the Church to respond appropriately to his misconduct, again over a period of many years. Ball’s priority was to protect and promote himself and he maligned the abused. The Church colluded with that rather than seeking to help those he had harmed, or assuring itself of the safety of others.

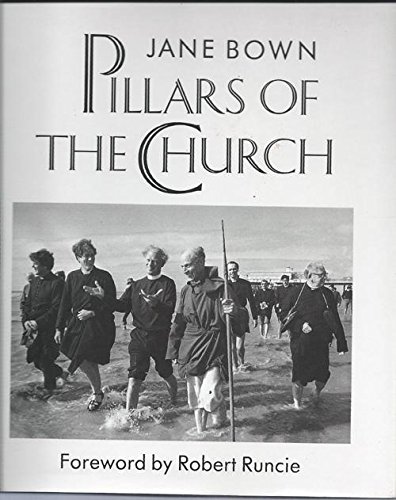

I’ve written about the Peter Ball case a couple of times before (here and  here) – he addressed an assembly at my school while I was teenager, and there was a summer during which a friend and I joined some others for a week at his residence on the outskirts of Berwick near Lewes. Ball, unusually for an Anglican bishop, was also a monk, and he affected a Saint Francis-like manner that appeared to embody spirituality, good humour, gentleness, and discipline. Before his police caution in 1993 (which allowed Ball to evade true justice for more than 20 years), many people regarded him as a saintly figure, although in retrospect his whole disarming monastic pose seems theatrical and even campy.

here) – he addressed an assembly at my school while I was teenager, and there was a summer during which a friend and I joined some others for a week at his residence on the outskirts of Berwick near Lewes. Ball, unusually for an Anglican bishop, was also a monk, and he affected a Saint Francis-like manner that appeared to embody spirituality, good humour, gentleness, and discipline. Before his police caution in 1993 (which allowed Ball to evade true justice for more than 20 years), many people regarded him as a saintly figure, although in retrospect his whole disarming monastic pose seems theatrical and even campy.

One passage in the review has the measure of the man:

Ball achieved the high regard in which he was held by convincing many to recognise him as a deeply spiritual man – a monk committed to an austere and authentic practice of his Christian faith. But any strong personal convictions were combined with a capacity for self-delusion, denial and manipulation. He vindictively continued to try to traduce the reputations of Neil Todd [the 1992/3 complainant] and Mr A for many years. He exploited the respect and the faith attaching to his position in order to abuse boys and young men, in the face of a professed celibacy. His household expenditure was reported to be extravagant but he continued to wear monastic robes long after he had resigned from his religious community. There was an essential dishonesty in his resigning as a bishop on grounds of ill health, which enabled him to receive a disability pension. There is no evidence at that time of any enduring disability and his campaign to resume clerical duties commenced only weeks after his resignation.

The review also notes that Ball declined to cooperative with the review, which “does not sit well” with his expressions of regret. There’s also the remarkable detail that Ball received a further suspended sentence while in prison, for harassing a witness by letter.

George Carey

The review is particularly critical of George Carey, who was Archbishop of Canterbury at the time of Ball’s police caution, and much of the media commentary has focused on this aspect. Carey’s plodding through the “Decade of Evangelism” was never very inspiring, and this scandal will now completely overshadow how he is remembered. In 1993, he described Ball privately as “basically innocent”, and the fact that Ball was able to discretely resume some clerical duties after his police caution sent out a message (amplified by media collusion) that the allegation had been trivial or even false.

I don’t believe that Carey acted with the deliberate intention of denying justice to a victim of abuse, but although “collusion” may seem harsh, the report notes that “cover-up and collusion fall on a spectrum that includes carelessness and partiality.” Carey appears to have resisted some early lobbying on Ball’s behalf by his twin brother, Michael Ball, but it’s clear that overall he was taken in by Ball’s “saint” routine, and that this amounted to gross negligence. The review notes the way Carey has tried to downplay his personal culpability:

Lord Carey admits that some mistakes were made but the extent to which he accepts any personal responsibility is limited. Almost every expression of regret is in the plural – “we undoubtedly let down the victims of Peter Ball” – and is tempered by a reference to the failures of the wider Church. It was “the Church of England (which) enabled Peter Ball to continue in ministry”. The absence of attention to Ball’s victims was a “widespread failure of the church“.

Michael Ball

One figure who has received little attention until now is Ball’s twin brother and fellow bishop, Michael Ball. The report reveals that Michael Ball advocated aggressively for his brother’s rehabilitation, admitting only that Peter Ball had been “silly”. When Archbishop Rowan Williams re-opened the file on Peter Ball in 2010, Michael Ball sent him an extraordinary letter accusing him of having “set out carefully and cunningly to destroy Peter physically, personally and in his ministry”.

The review also considers testimony that Michael Ball allowed his brother to impersonate him at certain events following his public disgrace in 1993, noting that “it appears to us extraordinary that a bishop should, at best, be so careless as to allow himself to be impersonated, and particularly to be impersonated by a former bishop who had resigned in the circumstances detailed above.”

Prince Charles

Peter Ball is known to have been held in high regard by the Prince of Wales, who has inherited his paternal grandmother’s enthusiasm for exotic spirituality. I remember that Ball had an autographed photo of the prince on display at his home, and the review notes that

Ball clearly intimates on many occasions, to Lord Carey and others, that he enjoys the status of confidant of the Prince of Wales. He ensured that Lord Carey was aware that he corresponded with the Prince… and that he visited Highgrove House. There are frequent references in Ball’s letters to Lord Carey and others to his attending royal functions and to meeting members of the Royal Family. Following the retirement of Bishop Michael Ball, the brothers lived together in a house which they rented from the Duchy of Cornwall after the Duchy had acquired the house specifically for that purpose…

There have been media reports that Prince Charles attempted to intervene on Ball’s behalf in 1993, although according to the review “we have reviewed all the relevant material including the correspondence passing between the Prince of Wales and Ball held by the Church and found no evidence that the Prince of Wales or any other member of the Royal Family sought to intervene at any point in order to protect or promote Ball”. It further notes that the Crown Prosecution Service “has publicly stated that it had neither received nor seen any correspondence from a member of the Royal Family when Ball was under investigation in 1992/93”.

In 2015, the Daily Mail‘s diarist Richard Kay wrote an article in which it was claimed that “the bishop’s principal entree into the Waleses’ household” had been none other than Jimmy Savile, and that Ball had “got to know Savile well” while at Lewes. No sources are given, and the story strikes me as highly unlikely: Savile had no particular association with East Sussex in 1980s, and Ball is much more likely to have to come to know Charles through church-related activities. Savile’s name does not appear in the review.

A network?

The review notes that Ball had associations with other priests who have committed sex abuse, and states that an “account of Ball abusing a 13 year old boy in the presence of [Colin] Pritchard and [Roy] Cotton led to one of the charges which he did not admit when imprisoned.” The review’s assessment is that

Most of those we spoke with would not go so far as to say that there had been an organised “ring” of abusive priests. However some felt that there had been particular issues relating to the Chichester diocese, where the conditions were right for “like minded” people to come together…

…There will be different degrees of organisation and association within a category of “organised abuse”. We have not found evidence of organised abuse in the sense that there were clear mutual arrangements between perpetrators to identify, groom and abuse victims. Sussex Police told us that they were reluctant to reach such a conclusion after their extensive enquiries into Ball’s conduct.

Time to return to another scandal?

Two years after Ball’s 1993 disgrace, the Church of England experienced another sex scandal: it was revealed that a charismatic young vicar in Sheffield had been a sexual predator of women. The vicar, Chris Brain, had achieved fame through his Nine O’Clock Service, which had been appreciated by the Church of England as a way to engage the youth. Carey said at the time that he felt “crushed and let down” by the revelations about Brain.

Because Brain’s predations were manipulative rather than coercive, his behaviour did not lead to any criminal sanction. However, this was also a problem in bringing Ball to justice, and it was resolved by determining that an Anglican bishop is a public officer. Ball was thus convicted of misconduct in a public office. If this applies to Anglican bishops, why not Anglican vicars, too?

Filed under: Uncategorized | 11 Comments »