From the website of George Conger, early last year:

The former Bishop of Gloucester, the Rt. Rev. Peter Ball, who was arrested in November 2012 on suspicion of child abuse, has not been charged following an 18 month investigation by detectives from Sussex Police.

On 28 Jan 2014, the Crown Prosecution Service said it was still considering the case against Bishop Ball, who was arrested in his Somerset home in November 2012 as part of Operation Dunhill. The bishop was reported to have been taken ill following his arrest.

…The late Bishop of Chichester, the Rt. Rev. Eric Kemp, was skeptical of the veracity of the charges brought against Bishop Ball. In his 2006 memoirs, Shy But Not Retiring, Bishop Kemp stated: “Although it was not realized at the time, the circumstances which led to his early resignation were the work of mischief makers.”

Here is a fuller quote from this passage, which appears on page 183:

[Ball] was not well received [as Bishop of Gloucester] and was not happy. Although it was not realized at the time, the circumstances which led to his early resignation were the work of mischief-makers. It was a very sad end to his ministry and his departure was a real loss to the Church which was, no doubt, what those who brought it about intended. [1]

This is somewhat enigmatic, although it seems to imply that there was more than one accuser.

And now, from the Guardian:

Peter Ball, the former bishop of Lewes and Gloucester, pleaded guilty on Tuesday morning to two counts of indecent assault relating to two young men and one charge of misconduct in public office, which relates to the sexual abuse of 16 young men over a period of 15 years from 1977-1992.

…On Tuesday, the Crown Prosecution Service allowed two charges of indecently assaulting two boys in their early teens to lie on file. The deal, hammered out in secret with CPS lawyers, means Ball will not face trial on perhaps the most serious alleged offences, which involved boys aged 13 and 15.

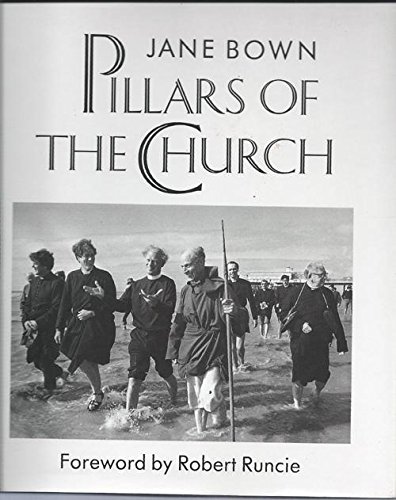

I can remember when the initial allegation against Ball was announced on the news towards the end of 1992, and I must confess that at the time I didn’t believe it. As suffragan Bishop of Lewes in the 1980s (as shown on the cover of Pillars of the Church, a 1991 collection of clerical photographs by Jane Brown) he had been a much-liked figure, noted for his warm humour, gentleness, and spirituality; in his monastic garb, he was also somewhat exotic. On one occasion he gave a talk at my high school, and when he mentioned that he accepted guests at his home who wished to experience something of monastic simplicity, a friend and I were intrigued enough to arrange a stay of a few days. His official bishop’s residence was quite comfortable, although I did take a peek at his bedroom and saw that it was kept bare, apart from a mattress. There were some other men staying in the house at the time, of various ages; they all seemed to be a thoughtful and happy crowd.

I can remember when the initial allegation against Ball was announced on the news towards the end of 1992, and I must confess that at the time I didn’t believe it. As suffragan Bishop of Lewes in the 1980s (as shown on the cover of Pillars of the Church, a 1991 collection of clerical photographs by Jane Brown) he had been a much-liked figure, noted for his warm humour, gentleness, and spirituality; in his monastic garb, he was also somewhat exotic. On one occasion he gave a talk at my high school, and when he mentioned that he accepted guests at his home who wished to experience something of monastic simplicity, a friend and I were intrigued enough to arrange a stay of a few days. His official bishop’s residence was quite comfortable, although I did take a peek at his bedroom and saw that it was kept bare, apart from a mattress. There were some other men staying in the house at the time, of various ages; they all seemed to be a thoughtful and happy crowd.

Ball at first denied the 1992 allegation, but then accepted a police caution in early 1993. That, of course, was an admission of guilt – and it had come only reluctantly, despite a statement in which he had mentioned his “great penitence and sorrow”. I was particularly taken aback that he had at first intended to brazen out the scandal with a harmful and cold-blooded lie, allowing his colleagues and friends to add to the victim’s pain and distress through well-intentioned but misguided expressions of support and sympathy that he knew that he did not deserve.

The caution, and the expression of sadness from the Archbishop of Canterbury after Ball’s resignation, left the impression that there had been some sort of unfortunate grope in a moment of weakness; however, a 2012 interview with the victim, by videolink from Australia, made it very clear that the abuse he had experienced aged 17 was over an extended period and had occurred within a context of calculated and manipulative behaviour [2]. The man, Neil Todd, was articulate and appeared to have made a new life for himself, but it was reported soon afterwards that he had died from an insulin overdose; the new reports in the wake of Ball’s guilty pleas now make clear that this was suicide.

It seemed to me obvious that it was highly unlikely that a man would give in to a predatory urge for the first time in his life at the age of 61, and we now know from reports published yesterday that the caution was also part of a deal that he hoped would mean that other allegations would not be looked into. We also now know that the historical complaint referring to a 13-year-old boy was made to police in 1996, which was while Kemp was still in post as Bishop of Chichester – and a good ten years before his “mischief-makers” slur against Todd appeared in his memoir. Kemp really doesn’t have any excuse.

Looking back, one of course looks for signs: I recall there was mention of an ascetic practice that involved naked prayer, which I didn’t quite like the sound of; and that he expressed the view that Billy Graham placed an overemphasis on sexual sin. In retrospect, the whole medievalising monastic pose seems theatrical, and the disarming other-worldliness an affectation.

In recent days I have written posts in which I have expressed scepticism of lurid tales about VIP sex abuse and murder in the 1980s. However, my view has always been that each case must be taken on its merits, and there is strong evidence that Ball was given special consideration because of his position – in other words, in this instance a “cover up” occurred.

UPDATE (16 September):

The Sunday Times has run an interview with Cliff James, who was assaulted by Ball the year before Todd. The article (with a different headline) is also available on the journalist’s website. It includes the detail:

The late Bishop of Chichester, Eric Kemp, reportedly told Ball to “stop inviting young men” to his house. But when Kemp wrote his memoirs, he described the boys who spoke out about their abuse as “mischief-makers”.

It’s not clear where this “reportedly” has come from – presumably it’s a piece of evidence that emerged in files that went to the police, and to which James was given access. Further:

James was 17 in 1991 when he learnt of an unofficial “youth scheme” developed by Ball, a close friend of the Prince of Wales. The “bishop’s young men” spent a year living with the cleric, doing chores and quasi-monastic work in his opulent house in East Sussex.

I’d describe the house as “plush” rather than “opulent”, although, as stated above, it appeared to me that Ball maintained some personal asceticism.

James could not have known that the bishop had engineered his programme to molest dozens of young people. He says he had concerns as early as the first interview, when Ball told him that he would have to have cold showers every morning, supervised by the bishop…

…The showers duly took place and gradually, says James, the “mind games and manipulation” increased, leading to beatings, always under the guise of religion, and increasingly sexual demands.

…After months of abuse James confronted Ball: “He physically recoiled from me: I think he was terrified I might speak to someone. He said he was worried about it all getting into the papers and he kept saying that everything had been consensual.”

I remember that he mentioned the benefits of cold showers to my friend and me, explaining that he was used to them due to having been to a private school. However, he did not make the suggestion to us that showers required supervision.

The claim about consent here is slightly mysterious – until 2001, it was illegal to engage in sexual activity with any male under the age of 21. James was 17, which meant that Ball would not have been able to rely on a defence of consent. The law was problematic and homophobic (being unequal with the lower age of consent for heterosexual and lesbian relationships), but its application to punish obviously predatory behaviour would not have raised many complaints.

UPDATE (8 October): Ball has now been sentenced to prison; more thoughts on this from me here.

Footnotes

[1] Oddly, although the book has been scanned by Google Books and can be browsed using the “Preview” function, searches relating to this page (and some other pages) no longer bring up results. However, I do remember this passage being visible previously.

[2] Some of this appears to have been known at the time; the conservative evangelical clergyman Tony Higton wrote an attack on Carey’s handling of the affair in the Christian Herald, in which – as summarised by Ruth Gledhill in the Times – he pointed out that “some of the abuses were allegedly in a religious context, which made them blasphemous” (“Carey ‘made light of bishop’s sin'”, The Times, March 24, 1993)

Filed under: Uncategorized | 1 Comment »