Staying with the subject of child-witches, Al Jazeera recently ran a documentary in its People and Power strand on children accused of witchcraft in Benin. While many of the cases of child-witch stigmatisation I’ve blogged about, mainly from Nigeria and Congo (and spilling into the UK), can be traced back to the teachings of powerful neo-Pentecostal evangelists, in Benin the phenomenon remains more closely rooted in traditional, non-Christian, beliefs and taboos around a child’s birth and development: a child born feet-first, or face down, or whose upper teeth appear before their lower teeth, may be regarded as evil and as a source of misfortune.

The consequences of an accusation can be dire: the documentary’s producer, Charles Stratford, speaks to Alidou Boukari, a traditional village healer who explains that if a child is thought to be causing misfortune, then various steps are taken. First, an exorcism; if that does not work, magic, and if that is ineffective, the child is expelled. However, should attacks continue, a child may be killed:

The killing is done by an elder. He takes the child into the bush and he kills it there. It is not done in the village. The practice goes on where the Bariba are. But no one will tell you who is doing the killing. Noone will tell you that such and such a person is the one appointed to kill the child. But there is always someone in the community who is old and spiritually powerful who does the killings.

Stratford also meets Nicholas Biao of the Family Protection Office in Parakou, who has been trying to change attitudes:

You don’t know when they go to kill a child. You can live with them for many years in the same area and children are being killed and you would never know. The phenomenon continues because it is cultural. It is tradition. It is deeply rooted in the mentality of the people… Despite efforts to raise awareness, the belief is passed from generation to generation. For example, when the executioner is old, he will train young executioners to take over the power of killings. This means it is perpetuated. … Personally, I have never witnessed a killing myself, but I talked to the executioners who told me how they do it.

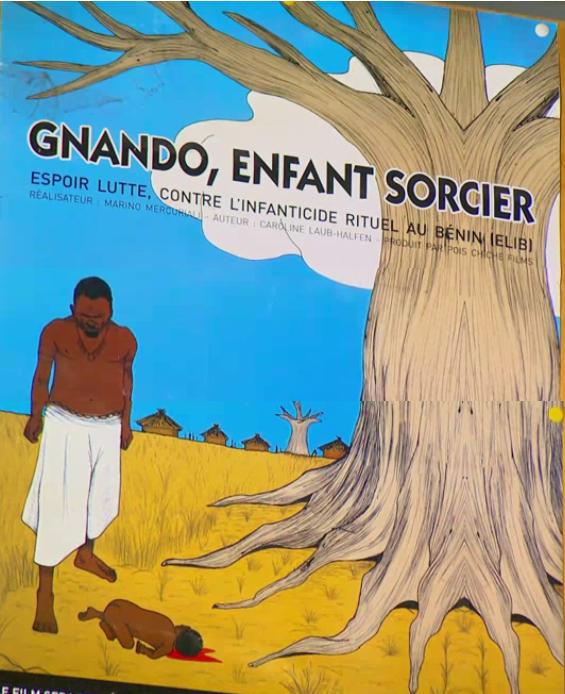

Biao points to a poster in his office (see above), which shows how a child is killed by being dashed against a tree. More commonly, though, a child will simply be abandoned.

In Akwa Ibom in Nigeria, there is now a State Child Rights Law which makes it illegal to accuse a child of being a witch; however, the government of Benin will not support a similar measure there, on the grounds that some children really are witches. According to Roland Djagaly, Assistant Director for the Department of Childhood and Adolescence in Atacora-Donga:

If this law was implemented one of the problems we would be confronted with would be that children could be accused rightly or wrongly. Not all natural laws are physical. A human being is a physical being, a spiritual being and witchcraft is highly spiritual. So beside the physical aspect the spiritual aspect supports our people in whatever they’re doing. That’s why today there are witches among children, witches among youngsters, witches among adults, witches among peasants, witches among intellectuals, witches among traders, witches among intellectuals.

…It doesn’t mean that we don’t have witch children, because today adults who are witches have a method of transmitting their power to children without the child’s consent. There are some children that are innocent, but due to circumstances are said to be witches.

Not everyone accepts this, though: Biao explains that some young couples will prefer to leave a village than to abandon their child, and Stratford meets some adults who have adopted abandoned children. He also talks to a mother who switched from vodou to Christianity after vodou priests told her that her disabled child had been responsible for causing her father’s death.

Watch the whole thing, entitled “Magic and Murder”, here.

Filed under: Uncategorized | 9 Comments »